Make Space Fgreat Again Play as Eurpeons Only

"Brand Space Great Again"

Nostalgic Amnesia on the Final Frontier

While delivering a speech to The states Marines in March of 2018, Donald Trump fabricated the following seemingly off-the-cuff, yet consequential, remark:

Y'all know, I was saying it the other 24-hour interval crusade we're doing a tremendous amount of work in space… I said "possibly we demand a new force, we'll telephone call it the space force." And I was not really serious, and then I said "what a bully idea, mayhap nosotros'll have to do that."

Afterwards that year in October, Kanye W visited the White House. Alluring a great deal of PR, he presented custom hats to Trump and his family unit. Of particular note were the hats that he gave to Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner— reading "Make Earth Swell Again" and "Travel Space Once again"—which played on the slogan Make American Neat Again (MAGA). Merely over a year later, Trump signed the Space Forcefulness into police within the larger 2022 National Defense Potency Act. This was closely followed by his Executive Club claiming Usa space mining rights, in spite of previous international treaties.

Why was Trump insistent on creating a new co-operative of the armed services, especially when information technology went against the wishes of and so many in the Pentagon? Why does its logo look and so like to Star Trek's Starfleet Command? Furthermore, why do and so many electric current private outer space ventures draw on nostalgia for the same era that Trump valorizes equally "great"?

I argue that what ties these together is a broader nostalgic amnesia for the 1950s and 60s, stripped of historical context and idealized as a menstruation of endless potential. I trace how the nostalgia that animates Trump, MAGA, and the Space Force parallels that of current ventures by the billionaire infinite class, ofttimes referred to as "NewSpacers" by scholars such as David Valentine.

In Lisa Messeri's ethnography Placing Outer Infinite, she describes the importance of nostalgia for planetary scientists scanning the cosmos for habitable exoplanets:

The search for an Globe-like planet is shot through with nostalgia — nostalgia in the precise sense of acute homesickness. Though much, perhaps impossible, piece of work would be required to undertake a "journeying home" to the Earth of the past that we think we remember, nosotros can, peradventure, detect an exoplanet that reminds the states of an Earth more habitable than today's or the future's World. The search for a habitable planet is nostalgia for an Earth we have never known. It is a search for an idealized dwelling.

Indeed, nostalgia is an agonized for the loss of something pure and past. Mad Men's Don Draper (during the height of the MAGA era) depicts nostalgia as "the pain from an old wound. Information technology's a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory lonely… [It] isn't a infinite ship. Information technology'southward a time auto… Information technology takes us to a identify where we anguish to go again… to a identify where we know we are loved."

Almost nostalgia involves some amount of distorting the past. When taken to extremes, however, it radically transforms the past through cornball amnesia, which Orlando Lee Rodriguez notes is when "the by, no matter how dysfunctional or painful, somehow becomes improve than the nowadays." This is non a nostalgia for the past itself, but rather for the imagined unlimited futures that are projected onto this era. Or, as French poet and essayist Paul Valéry distills it,

"The future isn't what it used to be."

Both MAGA and NewSpacer imaginaries are soaked through with nostalgic amnesia. The Mad Men era of the 50s and 60s is not only what Trump calls for his supporters to harken dorsum to, but it too represents the zenith of outer space accomplishment and optimism. Trump's imagery of this era invokes a mythical middle-class American dream of countless white sentry fences and well-paying jobs.

However, just as Trump's rhetoric erases the deeply problematic aspects of this era, so too does nostalgia for the golden era of space exploration. It omits the extreme social injustice of this period, including structural racism within NASA (every bit illustrated in the book and film Hidden Figures). It likewise ignores the fact that the space race itself was a technological and symbolic war machine boxing betwixt nuclear superpowers during a Cold War that brought humanity to the brink of annihilation.

There has long been a conflation of the militaristic and romantic aspects of space exploration. For example, when Star Trek starting time aired in 1966 it was four short years after JFK's "nosotros choose to go to the moon" speech and only three years before the Apollo xi moon landing. Information technology represented a utopian and Euro-centric federation of spacefaring in the "terminal borderland." Thus, it is no accident that the current Space Force logo so closely imitates that of Star Expedition'southward Starfleet Control, or that the Space Strength recruiting commercial is at times difficult to distinguish from the Space Strength satire on Netflix.

Every bit Chloe Ahmann and Vincent Ialenti betoken out, Trump'south slogan is more nearly the "brand" than the "great." So too is present action essential for NewSpacers. They are laser-focused on what to practise in the present to address unfulfilled by promises for cosmic futures. Performing this nostalgia is essential for asserting that this matters, that they thing, and that they will call into being the future they are entitled to.

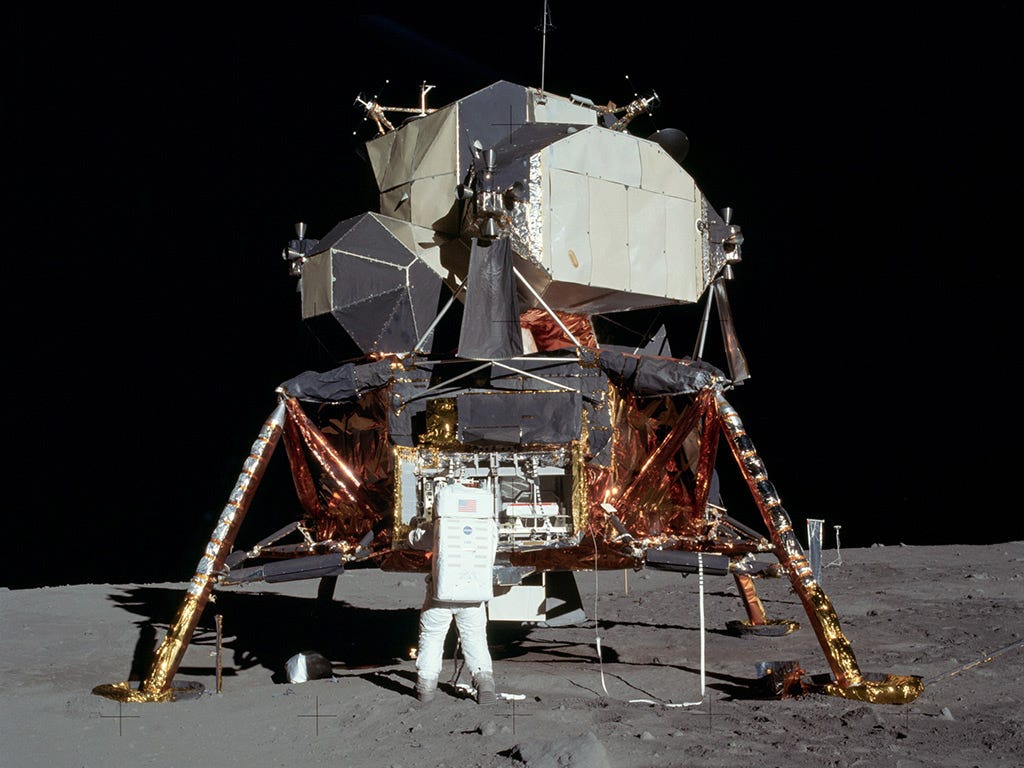

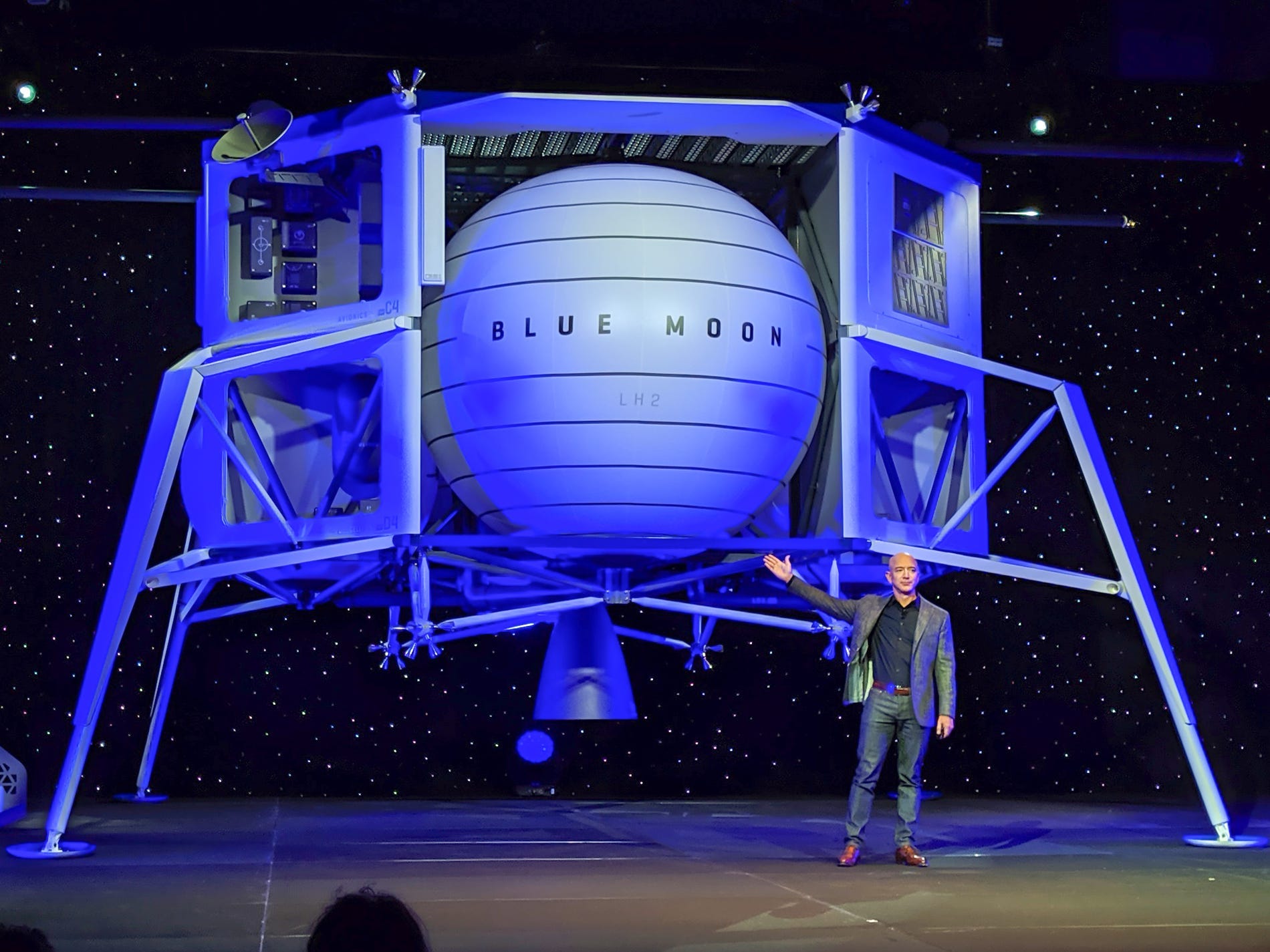

Nostalgia was specially apparent in Jeff Bezos' 2019 unveiling of Blue Origin's moon lander, which bears an uncanny resemblance to the Apollo lunar lander from 50 years prior.

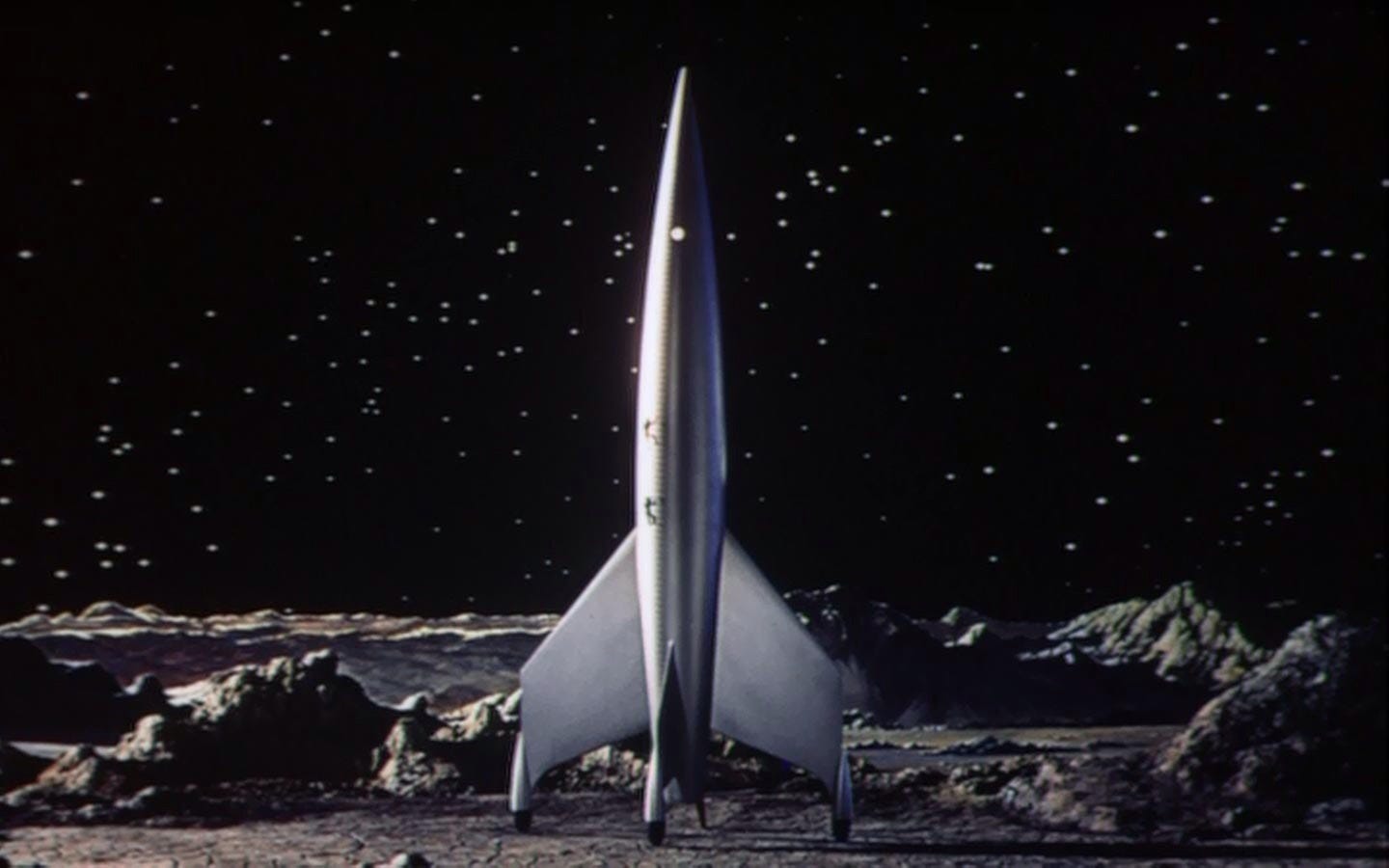

Elon Musk—the founder of SpaceX and the most influential NewSpacer—is particularly known for his nostalgic tendencies. For example, he based the Tesla Cybertruck on the 1977 Lotus Espirit/submarine motorcar from the James Bond motion-picture show The Spy Who Loved Me. Like Bezos, his nostalgia also applies to space ventures. Starship, the steel-clad SpaceX ship that Musk hopes volition transport people to Mars, looks like a Burning Human being-esque homage to rockets from 1950'southward science fiction films such as Destination Moon.

Equally with the majority of MAGA supporters, leading NewSpacers are made up of white males that serve every bit avatars for the self-made homo mythos: neoliberal heroes, infinite cowboys who have pulled themselves up past their space bootstraps. Indeed, a sense of lost masculinity is palpable in both of these groups, with NewSpacers longing for the days of test pilot astronauts with "the right stuff." They also sell grown-upward toys such as flamethrowers (read: space Remingtons) about which Musk noted, "obviously, a flamethrower is a super terrible idea…definitely don't purchase i…unless you like fun."

Furthermore, NewSpacer discussions about the purpose of space exploration betray more than a bear upon of loneliness, as though there is some deep fulfillment that eludes them on Earth. Musk often states that exploring and living on other planets should be almost more than solving problems, noting here that:

There accept to exist reasons that y'all go up in the morn and you want to live. Why practise y'all want to live? What'southward the bespeak? What inspires you? What do you love about the time to come? If the future does not include being out there amidst the stars and being a multi-planet species, I find that incredibly depressing.

This ennui is also reflected in Hollywood cinema. There is a long history of lost-in-space leading white men starring in films such as Gravity, The Martian, Ad Astra, Interstellar, and the iconic 2001: A Space Odyssey. Echoing Musk'due south existential angst, these protagonists are not seeking risk so much equally redemption for their breach from family unit and self. They anguish to resurrect what has already been consigned to oblivion. This is visually represented by empty expressions gazing into the void, as panel lights reflect off of their spacesuit visors while they ponder self-sacrifice, mortality, and the i thing that they have left: completing their mission.

Nostalgic amnesia is certainly not the only motivation for current space ventures. Indeed, younger generations are less probable to be motivated past such nostalgia (though I myself feel a touch of this from childhood infinite ice cream and space shuttle toys). However, for the older generation of NewSpacers, it is a key factor worth considering in low-cal of their disproportionate influence over mission goals and resource allocation.

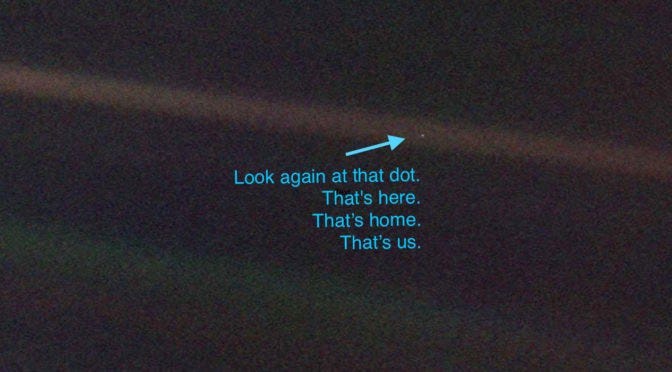

Outer infinite imaginaries too animate larger public understandings of humanity's shifting identify within and across Earth. Carl Sagan's poetic writing on the pale blue dot image inspired a generation to imagine how frail and precious our planet is, including the following passage:

Look again at that dot. That's hither. That'due south abode. That'due south us. On it everyone yous love, everyone y'all know, everyone yous always heard of, every human who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilisation, every king and peasant, every young couple in dear, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt political leader, every "superstar," every "supreme leader," every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there — on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

In dissimilarity to this overview consequence, the ultraview result (as coined by Deana Weibel) is what astronauts describe as a quasi-religious wonder induced past the vast multitudes of stars when viewed from space.

While Sagan's words encourage u.s.a. to temper heroic stories of past homo deeds past emphasizing the fragility of a atypical and precious Earth, NewSpacers tend to imagine a ceaseless final frontier promising personal, social, and species redemption—made possible past a profound cornball amnesia encompassing the entirety of colonial history.

Indeed, such redemption is projected onto innumerable potential 2d Earths, which serve equally proxies for 2d chances. Such willful mirages trivialize the importance of our one and just planet, while cartoon on the same confident logic at the heart of nearly all colonial endeavors.

They represent endless possibilities to start over, to leave behind all failures, to exorcise all demons. The promise that somehow we won't brand the same mistakes over again. That we can get it correct this time. That we tin rekindle the embers of a delicate, yet potent, feeling of childhood wonder.

That paradise lost, tin exist found once once again, in dark and distant places.

Source: https://medium.com/space-anthropology/make-space-great-again-9e91bc8aabb5

Post a Comment for "Make Space Fgreat Again Play as Eurpeons Only"